- Home

- Phoebe Wynne

Madam Page 2

Madam Read online

Page 2

‘You’re never a student?’ he answered with thinly veiled contempt. Rose checked the hardness in his eyes, the draw of his face.

‘No, I’m a new teacher there.’

‘Ach,’ he scowled. ‘You’re awful young.’

‘I am older than I look. I’ve been teaching for four years now, including training,’ Rose answered firmly.

‘That’s no’ Scotland, that place.’

‘Well,’ the woman came in brightly, ‘how lucky those girls will be, to have you teaching them. I’ll bet they’ve got a load of old cranks up there.’

‘Best of luck on your journey.’ The man turned back to the fridge as his wife smiled at Rose.

‘Will you be wanting anything else?’

‘No thanks,’ Rose answered flatly, preparing the change from her purse. ‘Just the tea.’

‘Here you are.’ The woman passed over the styrofoam cup. She shrugged a shoulder at her husband and gave Rose a comforting pat. ‘Never mind him.’ Rose glanced down at the woman’s small hand over her own.

She took a seat at the furthest edge of the cafe’s tables, her back to the couple. There, she pulled her suitcase into alignment with her feet.

Rose didn’t like being separated from her things. Only a few favourite books and a pile of her smartest outfits were stuffed into this shabby suitcase. The rest of Rose’s belongings – old volumes, clothes, bits of furniture – were packed in a small crate and would follow her, days later, to fill her new flat. Her first all to herself. The school had organised it, like they had organised her journey, her arrival, her new life.

She’d managed to stuff one goodbye card from her former pupils into her suitcase, though it was probably creased in all the wrong places now. An over-large piece of card, full of their untidy scrawl, half-correct phrases in Latin, small affectionate doodles. They’d even drawn a version of her head as a Roman bust on the front; she’d blinked with tears and laughter when they’d presented it to her at the end of last term. Well, she wanted to bring that little piece of evidence of her previous life into this new one – some soothing proof of her own capability. And inside that card she’d stuffed the treasured postcards that had decorated her old classroom. Places she’d visited, places her mother had saved up for them to see together, places she’d saved up for alone: Pompeii, Rome, Athens, Ephesus. A view here, a theatre there; a mosaic here, a sculpture there: to expand her mind, expand her horizons – one of her mother’s favourite phrases. And now these were places she was going to talk about, share with her new students and their fresh set of eager faces.

Rose didn’t yet have her timetable, but the Headmaster’s letter had informed her of seven classes of girls, one from each of the year groups, aged eleven to eighteen – just what Rose had been used to, and had trained for. At Caldonbrae Hall there were three ‘Junior’ years: the Firsts, Seconds and Thirds; then two ‘Intermediate’ years: the Fourths and Fifths; and finally the sixth-form’s seventeen and eighteen year-olds: the Lower and Upper Sixth. Rose knew that boarding schools usually had schedules busy with house duties and sports activities, but she’d been told that she’d settle in better with a lighter timetable for her first term.

Rose pressed the cup to her lips but the hot tea burned her mouth, dashing down her throat with a slip of pain.

She knew she would miss her old students just as much as she’d miss her old colleagues and their regular pub evenings or cinema trips. Last term, she and an Art teacher had watched Thelma and Louise on the big screen every Friday night for a month. It had been a nice life, and Rose knew that she’d think of them often, down in the sunnier south: even the white prefab of the squat school buildings, the concrete scrap of the courtyards, the shout of the students hurtling down the corridors.

The memories squeezed at her heart and she looked away.

Lucky, her old colleagues had insisted, picked out by an amazing school like Caldonbrae Hall, her career apparently speeding on ahead. Rose couldn’t have turned down this opportunity – the regret would have pursued her through her career. Now she’d have to learn to absorb the pride others had in her, to puff up this depleted balloon of self-worth inside her chest. Plus, her mother was right, Rose’s salary would cover the care she needed and more; and Rose could pay her back for all the things she’d done for her growing up, especially after her father had died. Rose smiled wistfully; perhaps in her own small way she was carrying on his academic legacy – not in his full lecture halls, but through short lessons in a brightly lit classroom in some tall building in Scotland.

A mechanical voice broke through her thoughts, calling over the tannoy, informing her of her delayed train.

Rose’s face flushed with alarm. By how long? The numbers flipped and Rose watched them change. Thirty minutes or more. But, she thought desperately, she wanted to see the place in daylight. It was already so late. Late in the day, late in the holiday. Term would start in two days – Rose needed more than that to settle herself in. But of course, she’d had no say in the matter. She worried about cutting it so fine – as if at any moment the school might turn around and send her away, tell her she wasn’t good enough; that it was all a mistake, just some cruel joke.

Rose hoped the car organised at the other end would be aware of any delay; she didn’t want to keep them waiting.

The sodden teabag slapped her mouth unkindly as she took another sip. It was lukewarm now and too strong – she flinched before swallowing the mouthful. Rose wondered whether she could ask the woman for a top-up of boiling water. Come to think of it, she needed the loo too. Maybe the woman could watch her suitcase while she went. Yes, she thought, she could even thrust the school’s prospectus in the front pocket and have it stare back boldly at the woman’s husband, just to taunt him.

A few hours later Rose arrived. Barely able to acknowledge the driver and his help with her suitcase, she fell into the back seat and into the final leg of the journey.

Once the car pulled through the gates and trundled up the long drive, Rose stretched out to catch her first glances of Caldonbrae Hall – her new home. But it was only passing shadows that touched her eyes through the glass, a night fog of steeples and turrets moving high above the car windows. She thought of the pictures in the prospectus, trying to fit the grey wedding cake of the photograph onto the hulking black mass that actually met her gaze.

‘Are we here?’ Rose asked the driver, although she already knew the answer.

He said nothing. She felt only the gentle push of the car rolling forward, around and towards the front entrance of the school. There Rose looked up for the relief of light from several windows – but her sight deceived her still, with sharp corners and two half-faced gargoyles bathed in shadow.

‘Good luck,’ the driver said as he dropped Rose’s suitcase heavily at her feet; he slammed the boot of the car with such force that she flinched.

The following morning Rose tried a walk along the peninsula, but the cold was tearing through her clothes, her jacket, nipping at the nape of her bare neck. She thought mournfully of the warm things she hadn’t packed: her knit cardigan, her favourite green blanket, at least one scarf. Even her dark hair taunted her by whipping around her face. Yes, the summer was certainly over, but the first days of September up here in Scotland were colder than she’d expected.

The night before Rose had been met by the porters and an apologetic note from the Headmaster: complicated circumstances meant that he was unable to greet her that weekend. A band of three gruff but helpful men took her across the dim light of the entrance hall through corridors and passageways, handling her single suitcase between them as they mounted the stairs to her new flat. At the door, they stood in her way. One porter handed over a brass ring of keys, her own singled out. Glimmering with nerves, Rose thanked them, stepping aside to slip into the low-ceilinged rooms; the floor creaked as she crossed the threshold. The porters watched her curiousl

y until she thanked them again with the close of her new front door.

Rose felt along the wall for the light switch. In the small kitchen a hamper was laden with food: a loaf of bread, butter, wrapped cheeses and meats, a box of eggs, a bottle of milk and a few tins of soup. Rose had bent to find the fridge, feeling her way around the cupboards, her heart beating with gladness at the generous and expensive gesture. In the basket was a note from Vivien, the deputy head: another kind apology at the unforeseen circumstances, a promise of the Headmaster’s introduction at assembly on Monday, and a full tour of the school led by Rose’s colleague Emma that first afternoon. The dining hall would open the first morning of term, so the food was to be enjoyed until then. A lonely beginning, she’d thought, but a welcome one. The porters would show Rose her new classroom the next day, and she’d hope to find Emma wandering about – in the Classics office, perhaps. She’d have to wear her tweed jacket again, for any potential first introductions.

But the next morning she hadn’t found Emma, or anyone of importance. The school was hauntingly empty, so she’d ventured outside into the bleary afternoon. She crossed ribboned playing fields, tennis courts, a pale green stretch of land interrupted by a long white pavilion. She peered over the furthest edge of the peninsula, the very tip of the broken finger and its rocky outcrops beyond. There were no others enjoying the grounds, but plenty of seabirds embedded in the ragged rock. Rose wasn’t used to that unexpected blue of the sea, the ruddy threat of the cliff – nothing at all like the bleached white cliffs and laughing sunlight of the south of England.

Pushing her hair out of her face, Rose couldn’t help but marvel now at the great monster of the school building, as if at any moment it might hoist itself up on its hind legs and unfurl, with thick turrets as black scales down its back, and crawl heavily into the waters below.

Inside its walls she could barely navigate from the wide entrance hall, the sweep of the double Great Stairs with a glass dome ceiling above. She wondered how she would learn all those corridors, those passageways, the rows of classrooms piled up on top of each other. Some dug out of the cliff below like dungeons, and others – like her own – high up and lofty with a fine view of the sea. Then the sudden caverns of the dining hall, the theatre, the chapel, a sports hall. All interconnected, sealed and folded into each other like dark tumours.

Rose was nervous, running through the lines of her speech she’d had to write for Monday morning’s assembly, a particular request from by the Headmaster. A speech about knowledge and the ancient world, he’d advised, to introduce her to the girls. Rose didn’t want to consider how unusual the request was – a test of nerve in front of the whole school on her first day, perhaps – and by now her printed speech was soft from the damp sea air.

The wind blasted at Rose again and she recoiled at the faint scream from the seabirds. She wanted to go back to her flat, somewhere in that mass of grey brick – her own new spot of warmth. She moved across the pitches, back towards the front entrance of the school, the grand swirl of the driveway and the majestic doors held wide open.

Open for the girls.

Rose stopped. She’d been outside long enough to miss the slow build of sleek black cars, backing far down the drive in a chain leading up to the front, depositing groups of girls and their trunks. There were squeals of laughter as the girls clasped each other before running into the building.

Rose watched them from her distant position, shaking with cold in her tweed jacket. She ought to have donned the old raincoat she’d seen hanging up in an alcove cupboard in her flat – from a previous resident, perhaps – but she hadn’t dared. The page of her speech shook too, its paper coming apart, the typed words blurring as she folded it smaller.

Beside the double doors one girl was standing still, separate from the movement of drivers and porters busy around her. She was a blur of dark hair and staring eyes, turned in Rose’s direction. Rose looked away, and was hit again by the cold blast of the wind.

Others soon crowded the main doors and the girl was lost among them, as was Rose’s only way back into the school. She didn’t want her students to see her like this for the first time. Could she get to the rocky beach near the headland, or even wander down to the gatehouse of the peninsula? But then, she’d have to follow the driveway, passing each car and many pairs of young eyes. Rose resolutely turned around, held in that position by some strange force, her ears full of the furious turn of the sea.

When she looked back at the school again – was it minutes, hours later? – the last of the black cars had slipped away from the main doors, now firmly closed.

2.

The next morning, Rose was the centre of attention in the great throat of Founder’s Hall. She fixed her eyes on the page in front of her, trying to ignore the mess of young faces beyond the platform where she now stood, all waiting for her to speak.

‘… Greece has been touched by heroes, gods and Titans, and its mythology leaves marks even today.’ The scrawl of her handwriting was unforgiving, her original version of the speech torn apart by yesterday’s damp wind. Last night she’d hurriedly rewritten it, remembering extra bits just before she stood to speak. ‘One such place is Delphi, where oracles were told …’

Three short rows of staff sat in a semicircle behind her on the platform. Rose could see the Headmaster – a surprisingly short man, she’d discovered when he’d introduced himself earlier – nodding along as she continued. But the animated words fell flat against her own ears.

Earlier that morning she’d knotted her unruly hair into a thick plait, before scrubbing her teeth and her face with the same anxious vigour. But along the main corridor she’d seen her mistake – Rose’s hairstyle matched the uniformity of the Junior girls’. They wore twists of pigtails or slim plaits down to their waists, tied with silver ribbons that matched the bows at their necks, which in turn finished off prettily their white cotton dresses, long-sleeved and full, buttoned at the wrist and down the back. They looked clean and pressed, just out of a storybook, for their first day back at school.

Rose needn’t have worried about finding Founder’s Hall for that Monday assembly, she only had to follow the swarm of girls filtering up the Great Stairs, along the first-floor corridor, up and around again towards the surprise of this gaping hall. There had been a short stream of Asian girls, too, one of whom tittered with amusement when she saw Rose stumbling with unfamiliarity towards the front platform.

Now, as Rose spoke, several of the Intermediate girls in the middle rows shuffled in their seats. They were an older but awkward upgrade to the Juniors, in the same high-necked white dresses with tight bodices holding in their adolescence. Cropped grey blazers were fastened around their shoulders; they wore no silver bows, their hair flowing free. But even the Intermediate girls were thoroughly outdone by the sixth-formers lining the back rows. These older girls gave a splendid array of pastel colours, each dress individual and seemingly bespoke. Long-sleeved and long-skirted, the designs played with narrow waists, a high neck or a collarless one, sleeves buttoned or finished with embroidery. Rose had gazed at the delightful picture they all made, touching her own blazer with a tinge of shame. Her favourite outfit, a dark cotton shirt-dress under a second-hand blazer with brass buttons, was nothing compared to these silk and lace creations she saw in front of her.

Rose ended her speech abruptly. A clap from behind infected the rest of the hall with a smattering of applause. She stepped backwards to a nod from the Headmaster, now beside her.

‘Thank you, Madam.’

Here again the Headmaster’s movements were small and perfectly balanced, gesturing at Rose to resume her seat. He smiled with his mouth, but his brown eyes were sharp and analytical. They matched the brown of his hair, which shone in the light, the shoulders of his frame soft and slight.

‘Ladies, what a wonderful introduction from our new head of Classics. Please welcome her warmly according t

o our Caldonbrae tradition. Thank you, Madam, we hope you will continue to delight us all for many years to come.’

Rose tried to smile, but worried that her face might crack as the hall now split into another ordered applause, a few young faces ducking in amongst each other to share a remark. The tall and angular deputy head, Vivien, took Rose’s place at the Headmaster’s side, a haughty expression fixed on her severe face. Stepping back to her seat, Rose wondered vaguely why the Headmaster hadn’t used her surname, and stuck only to this anonymous ‘Madam’ label.

To distract her pacing anxiety, Rose sat down and cast her eyes over the large hall. The long, high-walled gallery was set with heavy canvasses including several portraits of aging men – previous Headmasters, she assumed. Rose blinked at an over-large map of the British Empire; its coloured spread across patches of the world reminded her of a Roman Empire poster from one of her old teacher training classrooms. The most prominent portrait was of the Founder, who gazed over the entire hall with disapproval; his grey curled sideburns as thick as his eyebrows, one arm touching a pile of books and the other pressed firmly against his heart. Above him the hammer-beam ceiling was knotted with a darker wood, and around it the hall’s upper edge was marked with square windows. The soft morning glow would have been soothing if Rose’s nerves hadn’t been so frayed.

The deputy head was speaking now, her voice fluid and smoothly assured, somehow matching the curls of her steel-grey short hair.

‘And now we will say the school grace, read by the younger sister of Hope’s most recent head girl, Vanessa Saville-Vye.’ A small girl peeled herself away from an Intermediate row and strode towards the lectern, tripping up the few steps, her face screwed up with distress. Rose stood up with the rest of the staff. The Headmaster and his deputy stepped back to the edge of the platform, their heads bowed in respect.

From what Rose could see the girl was a pale thing, with a wisp of blonde hair around her head. A few of the teachers near Rose clasped their hands together as she grabbed hold of the lectern.

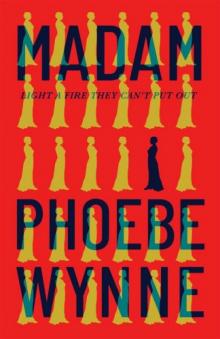

Madam

Madam